The Gulf of Fonseca

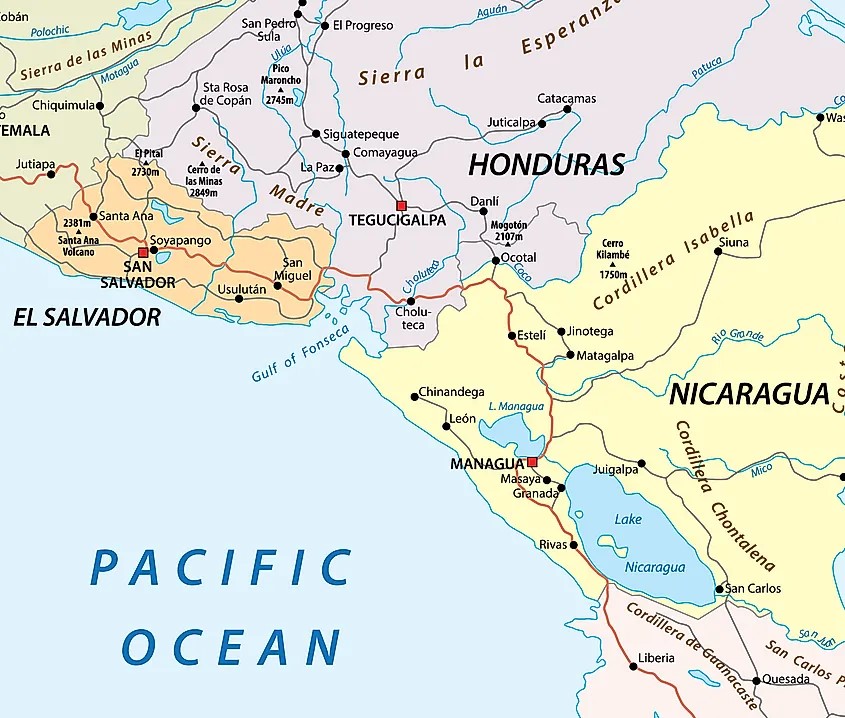

The Gulf of Fonseca, a part of the Pacific Ocean, is a gulf in Central America, bordering El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua. The Gulf of Fonseca covers an area of about 3,200 km2, with a coastline that extends for 261 km, of which 185 km are in Honduras, 40 km in Nicaragua, and 29 km in El Salvador. All 3 countries have been involved in a lengthy dispute over the rights to the Gulf and the islands located within.

The Gulf of Fonseca Dispute

Issues of sovereignty and access to resources in the Gulf of Fonseca arose quickly following Honduras’, El Salvador’s and Nicaragua’s independence from Spain in 1839. Upon independence, the respective boundaries of the three nations reflected the former administrative boundaries of the Spanish colonies. As early as 1854, the legal status of the islands located in the Gulf of Fonseca became an issue of dispute; the question of the land frontier followed in 1861. In 1972 the parties were able to reach an agreement on a substantial part of the land border between El Salvador and Honduras; only six sectors of the frontier remained unsettled. A mediation process initiated in 1978 resulted in the conclusion of a peace treaty in 1980. Under this treaty a Joint Border Commission was created to determine the boundary in the remaining six sectors as well as to decide upon the legal status of the islands and the maritime spaces. In the event that the parties did not reach a settlement within five years, the treaty provided that the parties, within six months, conclude a Special Agreement to submit the dispute to the ICJ. Accordingly, a Special Agreement was concluded on May, 24, 1986 requesting the Court to delimit the frontier between El Salvador and Honduras in the subject six sectors and to determine the legal status of the islands in the Gulf of Fonseca, and the waters of the Gulf itself. This led to the ICJ 1992 Judgement.

In terms of the land borders the Court relied on the uti possidetis juris principle, according to which the national boundaries of former colonies correspond to the earlier administrative borders of the colonies. With regard to the islands in the Gulf of Fonseca, the court focused only on those islands that were in dispute. The Court concluded that three islands were in dispute, namely El Tigre, Meanguera and Meanguerita. The Court found that El Tigre appertained to Honduras and Meanguera and Meanguerita to El Salvador.

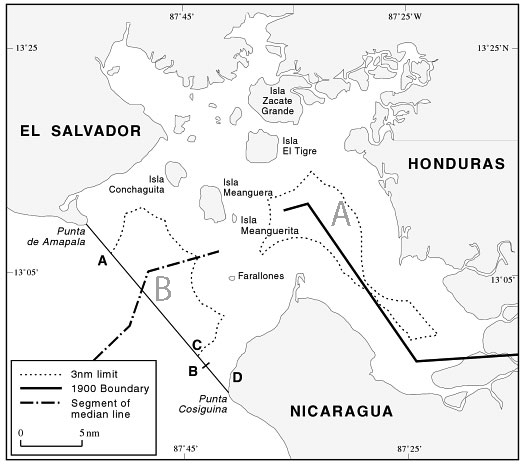

The division of the maritime spaces led to the unique tripoint arrangements we have today. The court decided that the Gulf of Fonseca was a “closed sea” and a “historical bay” which belonging to all three coastal States communally, with the exception of a three mile zone established unilaterally by each coastal State. At the time of independence from Spain the 3 newly independent countries inherited shared, communal undivided waters. This established a condominium, and determined that the three Parties shall maintain a tripartite presence in the waters while pending an official delimitation. The map below indicates the complexity of this judgement as it appears that there are 2 tridominiums labelled A and B, an inner and outer one.

The Court drew the closing line of the Gulf between Punta de Amapala and Punta Cosiguina and determined that the special regime of the Gulf did not extend beyond this closing line. This led to a unique border situation where in Zone B the shared tridominium waters meet the as yet unshared borders outside the gulf. Therefore, the three coastal States, joint sovereigns of the internal waters, must each be entitled outside the closing line to a territorial sea, continental shelf and exclusive economic zone. This is particularly important to Honduras that need safe access to the sea. The court decided it was for the states to decide the issues of ownership and economic zones outside the gulf. However, while not specifying any official maritime boundaries, the Court did vaguely grant Honduras a 3 nautical mile wide corridor extending from the closing line of the Gulf of Fonseca.

El Salvador was unhappy with the Court’s proposed solution and attempted to have the ICJ revise the 1992 Judgment a decade later, renewing the strained relationship with Nicaragua and Honduras as they both supported the original terms of the Judgment. El Salvador’s request was found inadmissible by the Court based on the presented facts.

Despite attempts at reconciliation in the following years, violence in the region continued due to disputes over maritime boundaries, trade routes, fishing zone access, and undercover drug trafficking in the region.

On 28 October 2021, Honduras and Nicaragua signed a treaty partially delimiting their maritime boundaries in the Caribbean Sea and in the waters outside the Gulf of Fonseca. This agreement partially delineates and affirms the boundaries between Nicaragua and Honduras as determined by the various judgments on its boundaries in 1960, 2007, and 1992. The 2021 Agreement has not entered into force. While it was ratified by Nicaragua promptly, Honduras hesitated and has yet to approve the treaty, whilst El Salvador did not engage.

Ongoing Issues

Conejo Island

El Salvador and Honduras continue to dispute the sovereignty of Conejo Island, a small island that can be reached by foot during low tide along the coast of Honduras. The island was not officially disputed until El Salvador filed its request to the ICJ for revision a decade after the 1992 Judgment. El Salvador was intending to modify the boundary along the River Goascorán from its present course to a historic riverbed. In doing this, Conejo Island would be within El Salvador’s control, which could further restrict Honduras’ access to the Pacific Ocean through the Gulf of Fonseca. However, with El Salvador’s claim being found inadmissible by the ICJ due to insufficient evidence, the island remains in Honduran waters. Despite this ruling, El Salvador has maintained their claim to Conejo Island in the intervening years.

From El Salvador

Visiting a wet tripoint is difficult, one’s perspective is affected by the country one is in. The Gulf of Fonseca is large and a lot of the shoreline is inaccessible. On IBRG CATEX-24 we had hoped to visit from both The El Salvadorean side and the Honduran island of El Tigre. The latter did not happen because we were unable to take a car across the border and due to the new and relatively unknown visa requirement for UK citizens to enter Honduras. This is Tripoint #29 for me. Other Americas tripoint visits are reported here

We therefore settled on gaining an overview from the summit of the Conchagua volcano. Following an increasingly unmade up road we reached a gate (a bit of a theme in this trip where the road was on the suitable for 4×4 vehicles. We set out on the 4 km walk with a steep 1 in 4 ascent. 70 minutes later we were at the top, where we needed to pay $6 to enter the viewpoint area.

The trip up was for me not enjoyable, hot and relentless. Luckily we managed to get a lift down which still took 30 minutes due to the road conditions.

From the summit of the Conchagua volcano.

The views were fantastic and gave an oversight of the 3 countries shorelines and the waters within the gulf.

Celebrations

Our third Central American Tripoint, and although we were unable to get closer this trip to the actual shared tridominium waters, the super views made up for it.

Next Steps

My visits to this tripoint are not over and I plan to view the tripoint from both Honduras and Nicaragua. Watch this space. We want to improve on this Class C visit.

Videos

Date of Visit: 02 December 2024